Projections of malaria seasonality for 2001 to 2050

MSM projections

The impact of climate change on the malaria seasonality was assessed by the MSM on a 0.5° grid.

MSM simulations have been performed for the five decades between 2001 and 2050.

The climate conditions of each particular decade is based on the three different

REMO ensemble runs, meaning that the "climate" of each decade is computed by the

data of 30 years.

The seasonality projections were carried out according to the

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) climate scenarios A1B and B1

(see page "Scenarios"). Each climate scenario is

including stochastic changes of the land use and land cover that are according to the Food and

Agricultural Organization (FAO). The scenario A1B is including stronger land use and land cover changes

than B1 (Paeth et al. 2007).

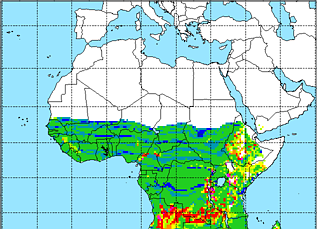

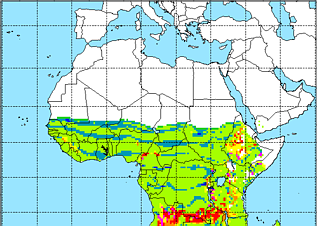

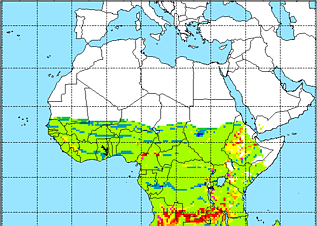

Changes in malaria seasonality

Largely due to the land surface degradation, REMO simulates a prominent surface heating

and a significant reduction in annual rainfall amount over most of tropical Africa in both

scenarios (see page "Data input"). As a consequence, the projections

of malaria seasonality show a decreased length of malaria season in most parts of tropical Africa,

i.e. most pronounced during the decade 2041 to 2050 (Fig. 1c). For example for large parts

of West Africa malaria transmission shortens between one and three months. For this reason

more frequent epidemics or even a malaria retreat are expected to occur in the Sahel. However,

increasing temperatures in highland areas of Cameroon, Nigeria, Guinea and Liberia

are partly leading to longer malaria seasons.

Higher temperatures and nearly unchanged precipitation amounts also cause an increase of

the malaria season in East Africa as well as in parts of Angola and Zimbabwe,

in particular in highland areas (cp. Lindsay and Martens 1998).

Dynamical MSM results according to different periods and scenarios

|

| Seas: 1960-2000 |

| ΔSeas: 2021-2030 |

| ΔSeas: 2041-2050 |

| a) |

|

b) |

|

c) |

|

A1B |

|

| d) |

|

e) |

|

B1 |

|

|

|

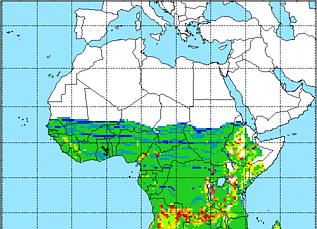

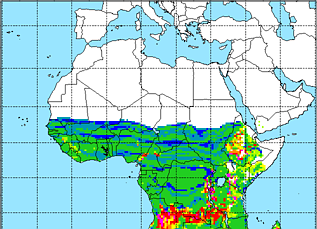

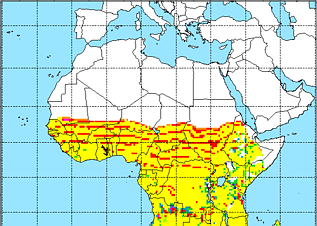

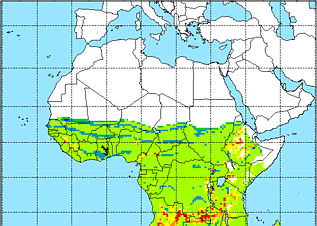

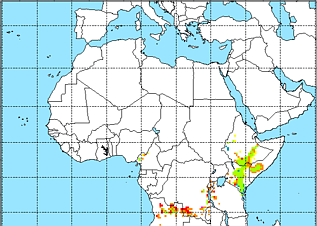

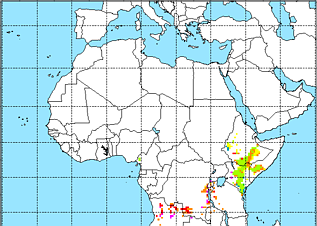

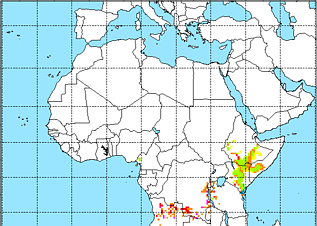

Fig. 1:

MSM simulations of (a) the length of the malaria season (Seas in months) for 1960 to 2000.

Differences in the length of the malaria season (ΔSeas in months)

between (b) 2021 to 2030 of the A1B scenario and the period 1960 to 2000.

(c) Same as (b) but for the last decade of the A1B

scenario (2041-2050). (d) And (e) same as (b) and (c) but for the B1 scenario.

|

| SSeas: 1960-2000 |

| ΔSSeas: 2021-2030 |

| ΔSSeas: 2041-2050 |

| a) |

|

b) |

|

c) |

| A1B |

|

| d) |

|

e) |

|

B1 |

|

|

|

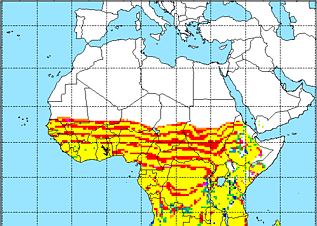

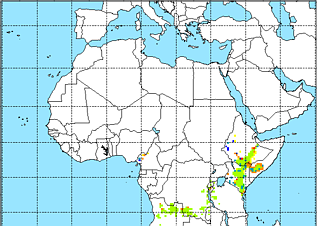

Fig. 2:

MSM simulation of the onset of the malaria season. (a) Start month of the malaria

transmission (SSeas) for 1960 to 2000. Differences in start month (ΔSSeas in months)

between (b) 2021 to 2030 for the A1B scenario and the period 1960 to 2000.

(c) Same as (b) but for the last decade of the A1B scenario (2041-2050).

(d) And (e) same as (b) and (c) but for the B1 scenario. Note, for

areas with two malaria seasons only results for the first season are presented. Note that

negative (positive) values indicate an earlier (later) start of the malaria season.

|

| ESeas: 1960-2000 |

| ΔESeas: 2021-2030 |

| ΔESeas: 2041-2050 |

| a) |

|

b) |

|

c) |

| A1B |

|

| d) |

|

e) |

|

B1 |

|

|

|

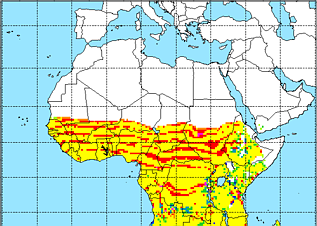

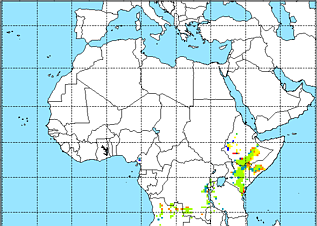

Fig. 3:

MSM simulation of the end of the malaria season. (a) End month of the malaria

transmission (ESeas) for 1960 to 2000. Differences in end month (ΔESeas in months)

between (b) 2021 to 2030 for the A1B scenario and the period 1960 to 2000.

(c) Same as (b) but for the last decade of the A1B scenario (2041-2050).

(d) And (e) same as (b) and (c) but for the B1 scenario. Note, for

areas with two malaria seasons only results for the first season are presented.

Note that negative (positive) values indicate an earlier (later) end of the malaria season.

|

| SSeas2: 1960-2000 |

| ΔSSeas2: 2021-2030 |

| ΔSSeas2: 2041-2050 |

| a) |

|

b) |

|

c) |

| A1B |

|

| d) |

|

e) |

|

B1 |

|

|

|

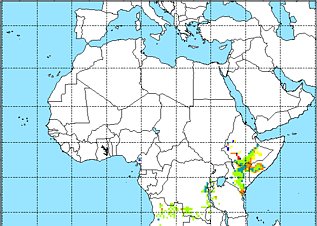

Fig. 4:

Same as Fig. 2 but only for areas with two malaria seasons

(SSeas2 and ΔSSeas2 in months).

|

| ESeas2: 1960-2000 |

| ΔESeas2: 2021-2030 |

| ΔESeas2: 2041-2050 |

| a) |

|

b) |

|

c) |

| A1B |

|

| d) |

|

e) |

|

B1 |

|

|

|

Fig. 5:

Same as Fig. 3 but only for areas with two malaria season

(ESeas2 and ΔESeas2 in months).

|